What makes for a great e-commerce business? Why do some online brands thrive while others struggle? One thing’s for certain: your P&L is driven by the fundamentals of your industry. The sooner you understand this, the higher your chances of achieving long-term success.

At Karlon Group, we help companies understand the drivers behind their P&L so they can make better decisions. Whether you’re selling beauty products or furniture, a key to winning is knowing your industry’s cost structure, where the big and sometimes hidden costs lurk, and how to address the financial challenges specific to your industry.

In this article, I’ll explain how different e-commerce segments stack up against each other and explore the hidden costs that can drag down profitability. I’ll also share strategies for managing these costs so you can stay ahead of the curve.

Why Profitability Varies by Segment

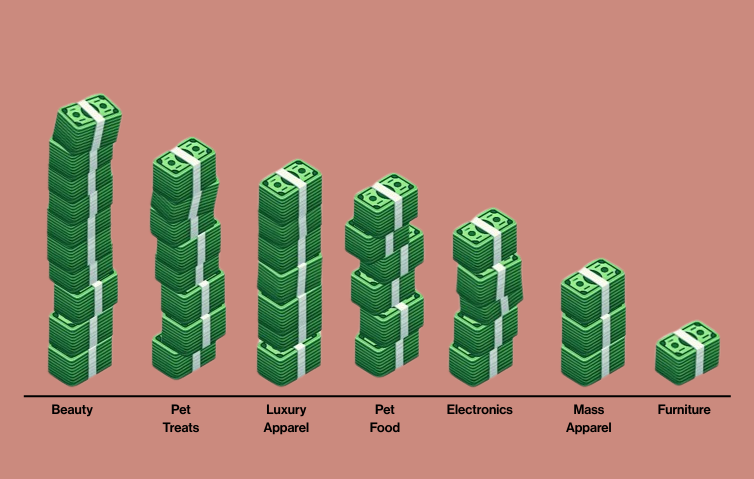

What does a highly profitable e-commerce company look like? Let’s start with a simple P&L benchmarking exercise. Below is a comparison of contribution margin before sales and marketing (CMBSM) across a handful of e-commerce segments. You can see right away that not all industries are created equal. Some industries have high CMBSM, others don’t. The important thing is understanding and managing the variable costs within your industry that ultimately shape your P&L.

Let’s start at the top of the list with beauty. Beauty tends to have a high CMBSM because product margins are high, returns are relatively low, and items are small and lightweight making them inexpensive to ship. If a beauty brand can find and acquire customers efficiently, it has a pretty good chance of surviving because its other costs are relatively low.

Now let’s look at furniture. Furniture tends to have lower CMBSM. One of the drivers is discounts. Furniture purchases tend to be highly concentrated around holiday promotional periods like Presidents Day, Memorial Day and Black Friday-Cyber Monday. Customers are willing to wait for a discount to make a purchase because the product tends to be expensive. In addition, limited brand differentiation and high price points make customers more price sensitive and motivated to seek a deal. The concentration of demand during promotional periods leads brands to compete aggressively for customers, which leads to higher discounts. This creates a negative feedback loop for furniture brands that erodes CMBSM. Another driver is return rates, which are higher because the product is expensive. Product margins are also compressed because materials such as wood, metal, fabric, and foam can be expensive and require skilled labor to assemble into finished products. Then there’s shipping. Shipping furniture is more expensive for obvious reasons – the products are bulky and heavy. Finally, even packaging is more expensive for furniture, because the products are bulky, fragile and come in a lot of different shapes and sizes.

But this doesn’t mean every beauty business wins and every furniture brand fails. While profitability is high in beauty, it’s a fiercely competitive industry that requires significant marketing spend to attract and retain customers. The potential for higher CPBSM and the ability to bootstrap attracts tons of new entrants. Beauty is also prone to rapidly changing trends, which make customers fickle and hard to retain over the long-term. Meanwhile in furniture, while contribution margins are low, average order values and profit dollars are quite high, which means a furniture business can still generate enough profit dollars to support itself.

Tackling Key Cost Drivers

Now let’s tick down the P&L and explore how you can tweak your business to offset certain margin-diluting costs.

1. Discounts

There are countless studies that show that discounts increase customers’ propensity to make a purchase. When used deliberately and carefully, they boost demand by creating urgency around a temporary reduction in price. Discounts are especially critical in industries like apparel, where fashion seasonality and trends drive a need to cycle through inventory frequently. But discounts can also be very addictive and once you start discounting, it can be hard to scale back.

Consider this: to breakeven on net revenue, a company offering a 20% discount must see sales lift of at least 25%. Sales lift is the amount of incremental sales you generate because you offered the discount. If you’re doing 20% promotions every weekend, what are the chances you’re seeing 25% sales lift consistently? And how do you even know? You have to also consider the pull forward effect of promotions. Your sales lift may be an illusion because oftentimes the lift you observe is not the result of new demand, but rather the result of customers pulling forward a purchase they would have made in the future. If measuring the sale lift is hard, measuring the pull forward is even harder. All this to say that discounts often don’t create the value – in higher sales not to mention higher contribution profit – that you think!

Unfortunately, a lot of companies are “discount takers” ‒ they can’t stop discounting because their competitors continue to do so. This is particularly true during around holiday promotional periods. Short of having a truly unique product or brand, which can take decades to develop or cultivate, many companies discount to compete. So what can a company do?

To reduce your reliance on discounts, one strategy you need to consider is reducing inventory. By lowering inventory on hand, you’ll feel less pressure to over-use discounts and you’ll see an almost immediate improvement in cash flow. This tends to be controversial because it can have a negative impact on sales growth. However, if inventory is managed closely and carefully, I’d argue this negative impact can mostly be mitigated. As an added benefit, reducing discounts can also improve the perceived value of your brand and drive higher demand over the long-term.

Another idea is to think more intentionally about the interplay between discounts and marketing spend. Once you see discounts and marketing spend as two forms of the same tool, you may identify ways to reduce marketing during your high discount periods and vice versa. The issue with combining aggressive discounting with high marketing spend is that it makes it very difficult to acquire new customers profitably – your CMBSM is likely to be low or negative during these periods. Over time this will reveal itself on your P&L as lower operating income and lower cash flow.

2. Returns

Returns are inevitable and costly. The true cost of returns includes not only the reverse logistics to bring returned items back to your distribution facility, but also rework costs, scrap costs, restocking costs, and customer service costs. At Karlon Group, we help our clients figure out the true cost of returns.The results are staggering and usually underestimated. A company can expect the true cost of a return to be 3x the cost of outbound shipping or more. Yikes.

But there are a few levers that you can pull to reduce return rates and the cost of returns. First, some industries can get away with charging restocking fees. Customers have learned to expect restocking fees in furniture and electronics, but not in beauty or apparel. A twist on this idea is to charge for returns (as a restocking fee or otherwise) if the customer requests a cash refund, but offer free returns if the customer accepts store credit for their return in lieu of cash. By pushing customers towards credit instead of cash, you reduce cash burn and encourage repeat purchases. To make this work, you need to develop a customer account system so customers can login and track their credits.

3. Outbound Shipping

For companies selling furniture, pet food, and sporting goods, where products are heavy or bulky, the cost of shipping to customers can be very high. Companies selling lower priced products, for example grocers, can also have high shipping costs relative to the average order size. The obvious lever here is to charge for shipping. But be careful. Customers generally expect free shipping for orders above $50. So if your average order size is in the hundreds of dollars, you may want to think twice. In these situations, I often advise clients to think about raising prices rather than charging for shipping directly. A 5% price increase on a $500 product can go a long way towards offsetting shipping costs. Another way to reduce outbound shipping is to expand your distribution footprint. This is less painful and more economical if you use third-party logistics providers (3PLs). Many of them charge for storage and pick and pack costs per unit, so if you divide your inventory between two 3PLs instead of one, you don’t necessarily pay more. However, there are three hidden costs to be careful about. The first is the inventory itself. With two facilities instead of one, you will generally need to invest in more inventory. The second is the time it takes to manage the inventory. With two facilities you have two locations to manage and twice the KPIs to analyze. This generally requires more time and effort from your planning and finance teams. The third hidden cost is transfer costs. Transfers between the two locations will be needed from time to time and these transfers come at a cost.

Conclusion

In the ever-evolving landscape of e-commerce, success often boils down to how well you understand and manage the key drivers of your P&L. Whether it’s rethinking your discount strategy or optimizing shipping costs, the ability to anticipate industry-specific challenges is what separates the winners from the rest. By paying close attention to your cost levers, you can improve margins, improve cash flow, and build a more resilient business. If you need help navigating these complexities, Karlon Group is here to provide fractional finance and accounting expertise to guide you toward more sustainable growth.

Notes:

In my definition of profitability, I use contribution margin before sales and marketing. Contribution margin focuses on the variable costs incurred to fulfill a customer order. However, it should be noted that my calculation of contribution margin also includes the cost of warehousing inventory, which is partially fixed. In my calculation of contribution margin, I exclude sales & marketing related costs because levels vary a lot between companies and sales & marketing spend can be thought of as discretionary.

The focus of this analysis is the P&L for e-commerce companies in different industries. There are other layers of industry analysis that I did not cover, including concepts like Porter’s 5 Forces and market size. There’s a lot of really valuable learnings from Porter’s analysis and in many ways these forces inform the industry P&Ls I discuss. Market size in my opinion is less important because all of the industry segments I covered are massive and it doesn’t make it any easier to scale a business if the total addressable market is $100B vs $50B.

About the Author:

Karsten Loose is co-founder and Managing Partner at Karlon Group, a fractional finance and accounting firm that helps companies build, scale, and optimize their finance and accounting functions. Karlon Group works with companies across SaaS, consumer, manufacturing and technology, offering a full suite of finance and accounting support tailored to each client’s changing needs.